- Home

- Ciro Bustos

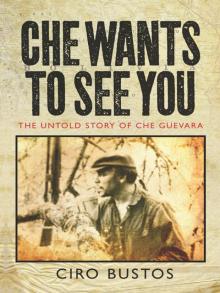

Che Wants to See You Page 2

Che Wants to See You Read online

Page 2

It was Che’s widow, Aleida, who helped set things in motion. She arranged for me to interview Alberto Castellanos, a Cuban who had been one of Che’s bodyguards and was a survivor of Salta. From the amiable Castellanos, I learned that Che had personally planned the Salta expedition and held high hopes for its success. He confirmed that Che had intended to come and lead the guerrillas himself once the foco was up and running. He had been captured and had spent three years in prison in Argentina, but had fortunately managed to keep his Cuban identity secret. Castellanos didn’t go too deeply into the causes of the debacle, but urged me to talk to several of the Argentine survivors, and he contacted some of them on my behalf.

I travelled to Argentina, where I met with Héctor Jouvé, who had been Masetti’s deputy. Like Castellanos, Jouve had been captured. He had spent ten long years in prison, however. For the first time ever, he spoke about what happened in Salta. As he did, a picture of horror began to emerge. It became clear that one of the main reasons the foco had failed was because Masetti had effectively gone crazy soon after he and his men had entered the jungle. He had become doctrinaire and bullying, and at the first signs of weakness amongst his untrained followers, mostly young volunteers from Argentina’s cities, Masetti saw crimes punishable by death. After impromptu trials in the jungle, he had two of them executed. While Masetti was busy terrorizing his followers, a local contingent of carabineros, Argentina’s rural paramilitary police force, was dispatched to the area where the guerrillas had installed themselves after reports of armed strangers had raised suspicions. As would occur a couple of years later in Bolivia, the guerrillas engaged the intruders in a firefight, prematurely alerting the authorities to their presence. Reinforcements were sent in to hunt down the guerrillas, and Masetti’s foco was quickly routed. Jouvé was the last man to see Masetti alive. He said that he suspected that Masetti had either starved to death where he had left him stranded or become lost, in the cloud forest, or else had committed suicide.

Jouvé spoke fondly of Bustos, whom he called ‘el Pelao’ – Baldy – and described him as Che’s point-man in Salta, someone who could shed a great deal of light on its long-buried history. He suggested I talk first to Henry Lerner, another Salta survivor, who was living in Spain.

In Madrid, I learned that Lerner had also been marked for execution by Masetti. Lerner had been spared at the last minute. It seemed less than coincidental, however, that Lerner, as well as the two other men Masetti had executed, Pupi and Nardo, were Jewish. Lerner was keenly aware of this fact but said he had always resisted the notion that Masetti’s enmity might have been motivated by anti-Semitism. But as we dug up the past, old suspicions returned. Like many of Argentina’s radicals of Lerner’s time, Masetti had come out of the Peronist movement, which had bewilderingly managed to straddle the political spectrum from the ultraright to the ultraleft. As a younger man, Masetti had belonged to the Tacuara, a virulently anti-Semitic Catholic group modelled on Spain’s Francoist Falange. Although he had since become a man of the Left, it seemed possible Masetti never reconciled his two extremes, and once in the jungle, the power he had acquired that brought out the worst in him.

After my meeting with Henry Lerner, Bustos told me to come see him in Sweden.

In Malmo, Bustos confirmed what Jouvé, Castellanos and Lerner had told me and added a great deal of important additional detail. He confirmed the connection between Salta and Che’s subsequent expedition to Bolivia, and revealed that Che had been planning an armed revolution in Argentina as early as 1962. Bustos, who had arrived in Cuba as an enthusiastic revolutionary volunteer in 1961, had been quickly recruited for Che’s Argentine project by Alberto Granados, Che’s old Motorcyle Diaries buddy. Granados had moved to Cuba after the revolution and had lived there ever since.

Bustos disclosed that he and the other members of the Che’s Argentina team had received their initial training in spycraft and the use of weapons in Cuba and then, following the Missile Crisis, had gone to Czechoslovakia and onto Algeria for more training. He acknowledged Masetti’s harshness and confirmed the brutal executions Massetti had ordered, as well as his own part in one of them. In the case of Pupi, the first victim, the execution was botched, he explained, and he had been forced to fire the coup de grace, shooting a bullet into the mortally wounded man’s head.

Bustos had survived the Salta catastrophe otherwise unscathed and made his way back to Cuba. There, Che had asked him to return to Argentina as his liasion with the leftist underground there, and had eventually summoned him to Bolivia, where fate awaited them both.

In the end, history is complicated. In the story of Che Guevara’s bloody demise in Bolivia, there has long been a tendency by survivors, as well as historians and analysts, to seek out culprits for what happened. The Bolivian army and the CIA agents, who secretly executed Che and many of his comrades, didn’t expound a great deal about what they had done after the fact. They didn’t need to, because they had won a battlefield victory, but they also had their war crimes to keep quiet about. For the Cubans, meanwhile, Che’s defeat was casually attributed to the faults of ‘others’, a potage that included the betrayals of some of the captured Bolivian deserters, as well as Bustos, for the drawings he had made in captivity. Others blamed the Bolivian Communist Party leadership, which had withdrawn its support for Che once he was in Bolivia, leaving him exposed and vulnerable. The area chosen for Che’s base camp at Ñancahuazú had been selected by the Party leadership and clearly had been highly unsuitable; many believed this was no accident. Any mistakes that had been made by members of Cuba’s secret services, meanwhile, not to mention the decisive role played by Fidel Castro himself, who had chosen Bolivia as the theatre for Che’s foco, were swept aside. The story that Ciro Bustos tells here is a candid one in which we can see that the final chapter in Che’s life was the result of a complicated alchemy that included all of the above, not to mention luck, or the lack of it, and, not least, Che’s own decisions. In the end, we are reminded, the outcomes of the mightiest of human enterprises are dependent on human nature.

Che Wants to See You is also the account of an extraordinary period in contemporary history in which thousands of young men and women around the world, inspired by Che Guevara and his Cuban comrades, believed they could change the world through armed revolution. They mostly failed, but left behind a remarkable legacy of shared idealism and sacrifice.

This book is ultimately part of that legacy, the journal of a life lived to the limit in pursuit of an ideal, with all of its consequences. There are many memories here, some of which are bittersweet jewels. Here is Bustos recalling how horseflesh, which he was forced to eat in order to survive in Bolivia, reminded him of the smell of Pupi at the moment he shot him dead. And there is the time when he overheard Che recite aloud verses from the Spanish poet León Felipe as they marched together through the Bolivian bush. It was one of the worst of times, but for Bustos, it is a most cherished memory of Che Guevara and of their shared revolutionary life.

Preface

This is a book about remembering, in two senses of the word. It is a memoir, not a biography, nor a book of history, political theory, or essays. It is the story of a stage in my life that goes off at tangents, into the future and into the past, when need be. The important thing is not my life, but what happened around it and what I witnessed. So writing in the first person singular is inevitable, because I am only recounting what I saw, heard, felt, listened to and read, as well as what I did, thought, and occasionally said. Nothing is presumed, added or invented. It is not a fictional account, these are real events, some of them small, and others transcendental, and they have all come together one by one to form my identity. There was no other way to tell this story than by looking frankly and openly inside myself; it is personal and unique. I am present throughout the book not for self-glorification, but to testify through all my senses to what was happening around me.

It is also a book written from memory. The avalanche of information

I collected over the years overwhelmed my lack of writing experience, and I found that although I had such and such a detail to hand somewhere, I couldn’t get at it without wasting days and weeks in a fruitless search. I eventually reached such a state of uncertainty, each doubt multiplied by hundreds of versions, that I chose to abandon all the material I had accumulated – cuttings, photocopies of articles and other kinds of documentation – and rely solely on my memory. A quote from García Márquez, which I read opportunely, supported me in my decision: ‘Truth is only what memory remembers.’

For dates and names, I have used about six books on the subject. The rest of the information was there, more or less organized for reference purposes, but always wrong, like coins hidden under tumblers in a magician’s trick. Memory, in any case, is like a coiled spring, waiting to be released. Sometimes fascinating things occur, comparable to the fishing technique of Laplanders who spend hours sitting beside a hole in the ice, with a fishing line rolled round their finger disappearing into the invisible waters, tugging on it gently from time to time, unperturbed, nothing happening, until, suddenly, a magnificent specimen emerges from the ice. I spent days and weeks with my mind blank, tugging the line a little and letting it go, until the whole spool unravelled unexpectedly. Sometimes it seemed as if someone was sitting inside my head dictating to me or, rather, that they were manipulating my fingers. Images appeared that I had not thought of since those days: meals, places, vehicles, situations, even music and smells. Naturally, not all the millions of moments that form a life are there. I read somewhere that the psyche filters bad memories that could harm the spirit, just as the body heals wounds.

It might seem as though some things are missing from the historical context, such as, for example, the nature of revolutions, and not just the Cuban. But to me this is a different topic, one that merits special analysis or scientific examination from defined political and ideological stances, and that is not the aim of this book, nor is it within my capabilities.

A large part of the book takes place at a time when almost everybody, including 90 per cent of its current detractors, loved the Cuban Revolution, even if the majority of them used it shamefully. There is no way anyone can accuse me of that. Nor can anyone surmise any financial interest on my part. For almost forty years I have refused any offer that would have meant an inappropriate use of the events and, particularly, any use of them for personal gain.

Comments about the form and style of the text are inevitable because I am not a professional writer. But some clarification is not only possible but necessary. For example, something that friendly pre-publication readers pointed out: Che’s Cubanized Spanish. While it is true he spoke with a pronounced provincial Argentine accent – that’s unquestionable – he always used Cuban vocabulary. Not even in nostalgic asides to friends did he indulge in Argentine vernacular. Also, some of the information revealed might make people uneasy, since it has been secret for decades. But it is no longer secret. Some of it has been disclosed by the Cubans themselves, in biographies or enemy documents, not forgetting the international actions of the Revolution’s troops.

There were names I could not find, lost in the whirlwind of time. Others, which no doubt exist in my books and documents, were simply left out. But, in any case, it was never my intention to produce a catalogue of events or a telephone directory. I would rather admit I don’t remember, as has often happened, than pretend or invent. Of course, there will be unintentional errors in names, dates, chronology, etc. Transferring memory to paper presupposes some poetic licence despite one’s best intentions, because images cannot be copied and pasted like new technology. They have to be turned into words and phrases with a certain harmony, and, if possible, elegance. And, yes, as happens when we recount our dreams, we can’t capture them accurately before they fade and become slightly deformed. I don’t think the errors are serious enough to distort the story, because I would have noticed, but in any case they would not be intentional or in bad faith.

Undertaking this task so long after the events, despite the insistent voices of friends urging me to do so earlier, has created a double slippage. First, potential readers – except for a few survivors – will be of a new generation, unfamiliar with the pre-globalization era, when more defined ideological camps implied a greater commitment to political struggles, even if only in writing, and therefore a greater recognition for the characters behind these words. These days, if it were not for the T-shirt industry, no one would even know what they looked like. Second, this book was written far from the natural environment in which the events took place, at the opposite geographical pole, and this has influenced my writing. Alone with my ghosts, without clear reference points, their lights and shadows are reflected on my keyboard.

Ciro Bustos

Malmö, April 2005

Part One

Cuba

1

Mendoza: Where It All Started

Mendoza is a unique city. The streets, all of them, are lined with trees. This is not a quirk of nature. It demonstrates the perseverance of its population and their creativity, traits nurtured in a culture inherited from the original inhabitants, the Huarpes, a peaceful tribe who loved trees and sat in their shade watching their crops, chewing on carob pods as sweet as their dreams. But dreams are closer to real life than fantasy, and real life depends on water. So they put their imagination and efforts into taming the water that gushed turbulently down from the snow-capped mountains some sixty kilometres away. The question was how to coax a modest tributary of brown water stemming from the mountain torrents into changing course. Tailoring the mountain slopes into channels meant not only hard work, but also rare engineering skills. And then, once down on the plains, what better way to distribute the water efficiently than by inventing the system of culverts which characterize the city of Mendoza to this day? It is the only city in the world to have irrigation ducts down both sides of every street, running parallel to the rows of trees spaced five or six metres apart that need watering once a week if they are to be kept fresh and healthy – a task undertaken by the people of Mendoza themselves, because without that there would be no plants, no vegetation, no fruit, and no trees beyond the native jarrillas, chañars and carobs, in whose shade the Huarpes rested.

The horses that the conquistadors brought, along with their primitive muskets and own natural brutality, played a defining role in the conquest of Indian land. But the gentle Huarpes, once their blood was up, and with early notions of guerrilla warfare, understood they had to learn from the invading enemy, and systematically stole the horses they saw frolicking happily in the grasslands. The horses, knowing on which side their bread was buttered, switched enthusiastically to the side of the indigenous people and, within a few years, breeding freely and increasing rapidly in number, had moved seamlessly into a privileged place in the tribal hierarchy: the chief or warrior, his horse, his wife. Over time, this combination produced a truly fearsome enemy for the invaders, and the Indian raid, the malón (a word with cynical implications: the mob, the baddies, the Indians, versus the victims, the goodies, the Whites), was their strategy for recovering stolen property. The horse, now naturalized, and running free in the wild, became a major factor in the ‘savages’, early success.

The Spaniards arrived with a considerable thirst on them, after a long journey exacerbated by thoughts of wineskins oozing good Spanish wine, trickling down their throats and over beards dry with heat and dust. So the sight of suspicious fields of neatly planted maize brought on a desire to replace them with vineyards stocked from their native Navarre, Catalonia, Andalucia or that magical sap from the banks of the Duero. Whatever the story, the contribution of these thirsty pioneers laid the foundation of Mendoza’s subsequent wealth. The settler population developed an unhurried pastoral existence, despite periodic attacks from other plains tribes who, I suggest, were after the casks of red wine, the remarkable product the barbarians brought, almost better than their own drink brewed from carob. The town grew

into a beautiful city soothed by two musical murmurs: the leaves of the trees in the mountain breeze, and the waters tinkling down the irrigation ducts along the streets.

I have enjoyed roaming these streets since as a child I first accompanied my father on his walks. And later, with my select gang of hooligan friends, I escaped from home at the sacred hour of the siesta, when the heat is overwhelming and, as the saying goes, only tarantulas and snakes dare cross the pavements. Jumping from one mountain of weeds to another, our expeditions took us through adjacent neighbourhoods, from the railway yards to the Cacique Guaymallén Canal (this good cacique’s invention before Mendoza was founded), round the outskirts of the city, through the large park and beyond to the foothills of the Andes. Our explorations were benign, never destructive or harmful. At most we stole fruit from homes where pear, medlar or plum trees lined the fences. We were real creatures of the city, exercising the freedom to enjoy it, learn its secrets, carve out an identity, and become citizens. As the writer Naguib Mahfouz said, ‘Our homeland is our childhood.’

Mendoza is the capital of the province of the same name, and its urban norms have been stamped on all the towns, villages and smallest of hamlets inside these vast 148,928 square kilometres – larger than Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium and Denmark put together. Over time, the basic features of trees and irrigation channels have come to characterize the whole region. So has prosperity, a prosperity built on the intensive cultivation of vines and the growth of the wine industry, now the fifth largest producer in the world, and also on the subdivision of land, helped by natural fertility and the dividends from its produce. Anyone who owns twenty-five acres of vineyard is a millionaire. While he enjoys his summer holidays in Viña del Mar (Chile), his land is overseen by a manager and his family, and worked by the humble descendents of the indigenous peoples mixed first with poor Spaniards and Italians, and later with immigrants from all over the world, attracted by the dream of conquering paradise by the sweat of their brow. But not everyone’s dream came true. After independence, the lands seized from the original inhabitants were distributed by the incipient local oligarchy exclusively among their peers, leaving the masses still in poverty. What’s more, the latter – artisans and soldiers, tradesmen and smallholders, agricultural labourers and gauchos – were dependent on the vagaries of the Buenos Aires Customs House, the first established centre of power, now representing the export interests of the British.

Che Wants to See You

Che Wants to See You