- Home

- Ciro Bustos

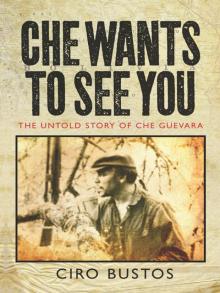

Che Wants to See You Page 5

Che Wants to See You Read online

Page 5

The May 1st celebration was the first mass demonstration I attended in Cuba. A million people, the papers said. In some ways it was like the Peronist demonstrations in the Plaza de Mayo, where I had never felt comfortable. Yet here the atmosphere was visually and psychologically different. Missing was that sense of menace that emanated from Perón’s descamisados, the lepers of Argentine politics as John William Cooke called them, who jumped and waved their headbands and ragged shirts, furiously banging their drums, as if to the scare the wits out of the Argentine bourgeoisie. In the Plaza de la Revolución there were no threatening dispossessed people fresh out of the shadows, smelling power. These were happy musicians, in a joyful parade.

The difference, of course, lay in the struggle to take power, in which the Cuban people had participated (although they didn’t all fight) while the Argentine masses had received it vicariously. The Argentines’ anger was still contained, their class-based rage unexpressed, compared to this pure joy of power achieved by passion and the sacrifice of lives. The only thing I remember of Fidel’s speech, which brought the event to a close, was the formal declaration of the socialist nature of the Revolution. It was, however, the most important bit. It opened a new and decisive phase in the struggle of the American people. A struggle I dreamed of joining.

But first I had to legalize my situation in Cuba. Picking one’s way through the mire of bureaucracy is always a prickly task, difficult anywhere. But in Cuba the bureaucratic machinery had been destroyed: no one knew anything; no one followed any logic or tradition; everything was new and pretty well improvised. Most positions of responsibility had been abandoned by people fleeing the revolutionary tide in panic, and taken over by youngsters with absolutely no experience. Administrators, company directors, heads of state enterprises and bodies vital to a functioning society were replaced by almost illiterate peasants and workers whose willingness and apparent honesty was their only skill. In some cases, they had absolutely no knowledge of the matters they were supposed to be dealing with. In others, one ideology was substituted with another – one caste destroyed and replaced by another diametrically opposed, implying a rapid and experimental reconstruction of a new order. Things now depended more on good will, luck and the energy that new decision makers brought to the job of deciding between the opportune and the opportunist, between the interests of the Revolution and urgent necessities. The chaotic situation was being run via ‘purity of origin’, that is, by ideological red corpuscles. The People’s Socialist Party, i.e. the Cuban communists, only recently incorporated into the triumphant ranks of the Revolution, now occupied the key posts. It filtered and selected personnel, including whole branches of the civil service, and had its eyes firmly set on the mechanisms of power. The rationale was that the PSP had to protect and strengthen the ranks of the Revolution, which had not only been openly attacked at the Bay of Pigs but was also being sabotaged daily both by Miami exiles and directly by the US government, which was diverting its efforts from military action to permanent terrorism.

The word gusano, meaning worm, became part of everyday parlance in describing counter-revolutionaries. In one of his speeches, Fidel talked of exiles being like gusanos in an apple, destroying the fruit of the people’s efforts and sacrifice. Miami was the dung heap where gusanos, who abandoned their country in its hour of need, ended up. Gusano attitudes, behaviour and even thoughts began to be detected, and dealt with like a pest, with ideological, verbal, written and armed pesticides. One method adopted for foreigners was to make them prove their political credentials, not freely and democratically, but in a sectarian and rigorously pro-communist way. Another more general measure was the creation of the Committees for Defence of the Revolution (CDRs), neighbourhood-watch organizations controlling the activities and lifestyles of the inhabitants of an area, block, or even street depending on the density of the population. They started life as a passive vigilante system, with no right to intervene, but morphed into a Hydra’s head, or Big Brother. Nothing escaped the gaze of the CDR. Depending on its make-up, it could help a neighbour with problems, or send him to prison.

Anyway, I needed to legalize my situation, and find a job. I began the exhausting task of running round offices and official bodies. I had no friends or contacts. We ended up in ICAP (the Cuban Institute for Friendship with the Peoples of the World). I met the director, my first senior official in the state apparatus, Ramón Calcines, a communist. He was quite young, and very handsome, like the star of a gangster film. He sent me on my way cordially, assuring me they would find something, we would be useful somewhere, all hands were welcome, etc. In these grave times for Cuba, he said, they were grateful to foreign volunteers. ‘But who are you, chico? See that little compañera, she’ll take your details, then we’ll see. Patria o muerte!’ The little compañera, a mulatta poured into clinging olive green, explained that I had to bring credentials from ‘my’ party, to add to my CV. Meanwhile she would find me something. I left wondering how I would get round my lack of credentials. The job the little compañera found me was temporary, but I had to start somewhere. The Cubans were hosting the first industrial exhibition from the Socialist Republic of Czechoslovakia and they needed designers, decorators, painters, etc. – a field where we could be useful. ‘And your credentials, mi amor?’ I explained that I had sent off for them – which was not exactly true – and that it would take time to get a reply. ‘But chico, without credentials, the Turquino looks tiny next to our problems!’ Turquino is the highest peak in the Sierra Maestra.

On the road to Rancho Boyeros there is an industrial zone with huge exhibition halls where the Czech exhibition was to be held. A Czech interior designer was charged with installing it. He was a tall, blond man who looked and behaved like a librarian, and spoke very basic guttural Spanish in a low voice while he polished his specs. Strictly professional, he indicated what he wanted and didn’t appear again until the work was finished. He soon showed signs he was satisfied, and even appreciative. He arrived at seven to find the place empty except for his foreign technical staff, and went round picking up scattered tools, waiting for the Cubans to turn up after eight, or even nine. When he got to our design table, he let off steam about the workers’ lack of punctuality. ‘They’ll never build socialism like this’, he said. The Cubans always had an excuse: they’d been on guard duty, in a political meeting, training with the militia, in a literacy class. And they really did seem very tired. They took on too many things and did none properly.

One morning, the Czech appeared with someone who was for me a transcendental figure: the Dutch documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens. I had admired him since I saw two of his most important films, Power and the Land (1934) and Spanish Earth (1937), at the Cine Club in Mendoza run by my Jewish friend David.

The ‘Flying Dutchman’, as this incomparable man was known, had studied optics before he became a filmmaker and was a specialist lens maker. He chose not to stay at home quietly in his prosperous family business, however, preferring to get involved in the century’s major social and political upheavals. A tall man of about sixty, with unruly greying hair, he was filming the installation of the exhibition. He said hello as the Czech introduced us.

4

Starting Work in Cuba

The Habana Libre hotel in Vedado, on 23rd Street and L, was the heart of extra-revolutionary activities. Fidel, a leader without a home, could be seen in the early hours going up to the top floors where he spent the night. The guests, foreigners for the most part, wandered about till late in the large carpeted salons, interconnected by Hollywoodesque staircases. Bellboys in red jackets with gold braid could be seen attending to awestruck campesinos on delegations from the interior to an assembly on the agrarian reform, or children from Oriente province on a visit to the capital, or giggling schoolgirls with starched cuffs on a nursing crash course, or youth brigades holding meetings by the lifts. An atmosphere of supercharged subversion filled the lounges and corridors, dislodging the privileged decadence of the loca

l elites and the omnipresent pre-packaged taste of the gringos.

Joris Ivens was staying at the Habana Libre. He asked me to help with the captions on his documentary, and we formed a bond. It was a reverential relationship on my part, and on his, I think, due to a need to keep the all-consuming Cuban reality at arm’s length, and talk to someone neutral yet just as amazed by the tropical exuberance. He spoke Spanish like an American but we understood each other perfectly. Interested in what had brought us to Cuba, he suggested we go to his hotel ‘where anybody who is anybody goes’. So, that same afternoon I walked the couple of blocks from the Colina and disappeared into the carpeted bowels of the Habana Libre. Whenever I met him after that, he was always with someone important. One night he introduced me to a woman in militia fatigues. She was Argentine, not Cuban. Her name was Alicia Eguren, the wife of the Peronist leader, John William Cooke. Alicia was cordial though quite curt and very inquisitive, as if she needed to ascertain which camp you were in. Not long afterwards she invited us to meet her husband up on the fifteenth floor, where they had a suite with large windows overlooking 23rd Street. Gordo Cooke, also in militia uniform, with a long beard that lay on his chest when he bent his head, had an unlit cigarette butt between his lips and ash splattered over his stomach. He was very nice and friendly. We were quickly on first-name terms like old friends, although I found it a bit disrespectful. To avoid misunderstandings, I made it clear I was not a Peronist but he was not interested in past affiliations; what mattered was the future. We talked until midnight. After that, whenever we met Alicia, we went up to see Gordo. Alicia was a kind of advance guard fishing for Argentines, who were then sucked up into the necromancer’s cave. Our friendship with her developed on the ground floor, in the hotel’s lounges and cafés, and with Cooke on the top floor, among Argentine newspapers, magazines, books and his own writings, scattered all over the floor. The soles of his campaign boots were as shiny as sugar cane, or even shinier thanks to the plush carpets covering his habitat. When I asked about Che, Cooke said Che was why they were there. Alicia was more emphatic. ‘Che is mine!’ she said. For an Argentine, she boasted, all roads to Che passed through her.

One evening the hotel hosted an exhibition of blindfold chess, organized by Miguel Najdorf, an Argentine grandmaster and world champion in the field. Originally from Poland, he was in Buenos Aires at a chess tournament when the Second World War broke out and was the only member of his family to survive the Nazi death camps. I recognized him from a fleeting encounter with him and his wife on a Number 60 bus in Buenos Aires.

A section of a large salon on the ground floor had been cordoned off. Inside were several widely spaced rows of tables. The challengers were seated on one side. On the other, blindfolded, was Najdorf accompanied by an assistant who brought him a chair if he wanted to sit down. The assistant called out the number of a table, the room fell silent; the challenger called out his latest move. Najdorf, deep in concentration, repeated the sequence of moves already played then made his move, which his assistant executed. The audience sighed with relief while the maestro moved on to the next of the thirty or forty challengers (his record was fifty-four) and repeated the miracle. At the end of the second row of tables, immersed in his game, was Che. It was only the second time I had seen him.

A couple of weeks earlier, I had read about an event commemorating the Spanish Civil War to be held in the Galician Centre, a baroque building on the corner of the Parque Central. Che would be there with General Enrique Lister, one of the great symbolic figures of the Spanish Republic. There was a huge crowd at the entrance. The room was long and narrow, crammed with rows of seats already occupied, and people standing against the walls, in the corridors, and sitting on the window sills. The ceiling fans were working overtime trying to recycle the air, but it was like stirring soup in which the audience were cooking.

Lister recalled the Civil War: the people’s militias, the role of the Communist Party, the International Brigades, and the support given by the USSR. Then Che spoke about the atmosphere in his family when he was a child, sitting round the wireless listening to news from Spain, as if the tragedy was affecting them personally, like all Argentines and other Latin Americans whether they were descendents of Spaniards or not. It informed his belief in the invincibility of the people’s struggle if its leaders have the same level of commitment, sacrifice and unity, over and above ideological schisms. He ended by paraphrasing an Antonio Machado poem and offering Lister his pistol if that same will to defeat Francoism would lead him to take up the armed struggle again. Che’s speech was not demagogic. His aim was not to persuade anyone or to milk applause. He spoke to say things he believed in or, at least, dreamed of.

Now here he was in the hotel, in front of his chess board, deep in thought, jotting things in his notebook after every move. In his well-worn fatigues, shirt outside his trousers, caught at the waist by his cartridge belt with his pistol on the right, the pockets of his shirt stuffed with papers, cigarettes and pens, his dusty unpolished boots, and his beret on the floor, between the legs of the chair. A woman who, like the crowd of us crammed together in front of him was not watching the game but Che himself, slipped under the cordon in a gesture of daring – or lack of vigilance by his bodyguard who was nowhere to be seen – knelt beside him, picked up the beret and handed it to him politely. Che, surprised but courteous, thanked her, but a few minutes later, with a sideways glance at his audience, put the beret back on the floor. The match ended with the hopes of most challengers dashed, Che’s included. In this particular battle, the strategist in chief was Najdorf.

One day Joris Ivens introduced me to a Mexican anthropologist, who was to be instrumental in finding me work. The National Institute for Tourist Industries (INIT) – one of the bodies created by the Revolution – wanted to build a country-wide tourist infrastructure and invest in new areas. It decided to revive traditional handicrafts that were of little practical use but had anthropological value and would generate jobs for local people. Ornaments made of hemp, shells and precious wood were common in Cuba, but in Oriente province there was also an original pottery-making tradition. It no longer made everyday utensils but the INIT wanted to revive it to make ceramic handicrafts. The Mexican girl knew the head of the project. He had asked her to study the possibility of setting up a workshop in Holguín, a town on the north coast of Oriente. The problem was that her already limited anthropological knowledge was theoretical, and she knew nothing at all about making clay pots.

Coincidentally, I had worked with ceramics on two occasions and had gleaned a basic knowledge. A fellow student at Mendoza Art School also attended the university’s School of Ceramics and he used to bring his creations round to my house. I got interested in the technique and ended up going to the workshops with him. I watched him prepare and apply varnish, glaze and various other combinations, depending on the desired degree of plasticity and hardness. Later, in Buenos Aires, I helped a colleague of my wife’s build an elaborate circular pottery kiln, with saggars (refractory containers) and moulds for liquid clay and clay paste, so we could produce whole series of pots by casting.

The Mexican girl thought she had won the lottery. She told me her boss was interested in my know-how. We went to see the project director, a sweaty Swiss weighing 120 kilos, in black suit, shirt and tie, wiping his brow with a handkerchief. I explained I was not a professional technician, that my knowledge was purely empirical. He seemed to have sussed the calibre of the staff he already had, and after a good chat decided that, compared to them, I was a genius. He offered me the job of running the handicrafts workshop in Holguín. This meant leaving Havana and potential contacts, but it also meant getting to know the interior of the island and the real Cuban people: the campesinos, the guajiros. What’s more, Oriente was the cradle of the Revolution. I took the job.

There was a diesel train that took ten hours to do the 700 kilometres between Havana and Holguín, but it was worth it. Going out into the countryside is to begin to know

Cuba. The modern world of Havana, luxurious and fickle, disappears as you leave the city limits. The towns and cities of the interior are decidedly colonial, with a marked African influence, not only in the people, as in Havana, but in the streets, the houses, the balconies with washing hanging, the galleries, verandahs, raised pavements, signs, shops, curiosity and noisy brouhaha.

Holguín province seemed a little different, and I soon realized why. It is an agricultural region like most of Cuba, but the land is richer, with meadows, woods, beaches, large sugar mills and a semi-feudal society based on sugar cane. It also has the island’s most important nickel reserves. The city of Holguín is orderly and quiet. The poor – cane cutters and seasonal labourers in the sugar mills, and a whole range of unemployed, underemployed and destitute – have been pushed to the southern outskirts of the city, to a huge shanty town made of yaguas, palm branches and bark precariously tied to poles for the hut roofs and walls, and stones to hold the thatches down.

The first thing I did after arriving at my Holguín hotel was to go out and get my bearings. The city was built round a central tree-filled square, with paved roads stretching for two or three blocks, more built up to the north away from the highway. It seemed very pleasant, but there was not much to see. I went into a café for a coffee, my breakfast in those days. The people who ran the café were my first friends. The second thing I had to do was sort out the so-called infrastructure of my new life.

Che Wants to See You

Che Wants to See You